A Canadian singer contends she is the starlet reincarnated. Although many will find the claim outlandish, she has a staunch supporter in Malibu psychiatrist Adrian Finkelstein.

![]()

Robert W. Welkos | Los AngelesTimes Staff Writer

HER name is Sherrie Lea Laird. She is the lead singer of a Canadian rock band called Pandamonia and the divorced mother of a 21-year-old daughter.

But throughout her life, the 43-year-old Laird contends, she has also been someone else: Marilyn Monroe.

Laird’s assertion that she is the reincarnation of the late Hollywood icon is sure to be dismissed by skeptics. But it has found an ardent defender in a Malibu psychiatrist named Adrian Finkelstein, who said he uncovered Laird’s previous existence after placing her under hypnosis as part of a highly controversial therapy known as “past life regression,” in which patients recall their past lives as a way to deal with problems in their current lives.

“In science, and I’m a scientist, we end up believing in what we prove scientifically,” Finkelstein said in a recent interview. “I established through research that Sherrie Lea Laird is the reincarnation of Marilyn Monroe.”

Finkelstein is an author and lecturer who, before journeying into the realms of spiritual healing and New Age therapies, was schooled in traditional forms of psychiatry, graduating from the prestigious Menninger School of Psychiatry in Topeka, Kan., was a volunteer instructor in UCLA’s department of psychiatry in the early 1990s and is currently accorded privileges to practice at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, where he occasionally consults on hypnosis techniques.

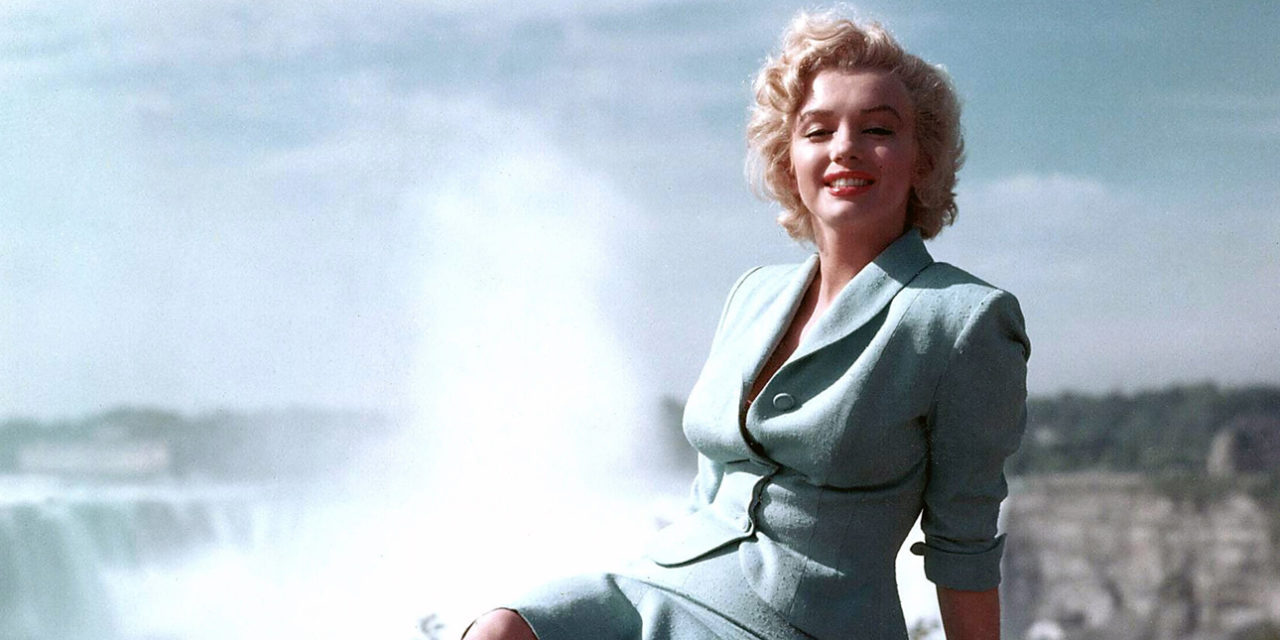

His videotaped sessions with Laird — who bears little resemblance to the late screen legend — are recounted in a new book he wrote titled “Marilyn Monroe Returns: The Healing of a Soul.” Speaking as “Marilyn,” the hypnotized Laird recalled love affairs with John and Robert Kennedy, including a tryst with JFK in the White House; she said JFK told her state secrets about Fidel Castro and Cuba; and she gave details about the actress’ death at age 36 from a drug overdose on Aug. 5, 1962, dismissing conspiracy theories that Monroe had been murdered.

Neither the American Psychiatric Assn. nor the American Psychological Assn. have taken an official position on past life regression therapy, but it’s not considered a mainstream therapy.

Critics, though, say the process can leads to patients incurring false memories, often as a result of intentional or unintentional suggestions of the hypnotist. As a result, skeptics say, these accounts are difficult if not impossible to prove.

Steven Jay Lynn, a professor of psychology at State University of New York at Binghamton, who has published more than 250 books, articles and chapters on hypnosis, memory, victimization and psychotherapy, said past life regression therapy “can be very comforting to people, and quite possibly helpful, but that doesn’t mean they’ve experienced something that was a residue of an earlier life.”

Too often, Lynn said, patients and their therapists can become emotionally invested in trying to uncover a past life experience and are therefore susceptible to interpreting the situation in a way that confirms their beliefs.

“It’s not a fraud — people genuinely believe they have experienced past lives,” he added.

Benefits of therapy

THOSE who practice past life regression therapy say it can make all the difference for some patients. “It really can help to heal or cure or alleviate mental and physical symptoms,” said Dr. Brian L. Weiss, a graduate of Yale Medical School and chairman emeritus of psychiatry at the Mount Sinai Medical Center in Miami, who said he has spent 26 years conducting past life regression therapy on some 4,000 patients.

A patient with persistent neck problems may recall being hanged in a past life, while someone afraid of heights may come to believe they were thrown off a castle wall in the 15th century. Understanding the root of these seemingly unfounded fears allows patient to confront and overcome them, he said.

Although many dismiss the notion that souls, or spirits, can be reborn in a new body, Weiss said it’s a concept that is widely accepted in the East and elsewhere. He also said that many in the U.S. believe, even if they might not like to publicly admit it. A national poll conducted in 2004 for Fox News by Opinion Dynamics Corp. showed that 25% of Americans believe in reincarnation.

“It’s not just Hindus and Buddhists,” Weiss said. “There is a Jewish tradition and Kabbala. Mystical Christianity. Plato believed in it. Ancient Greeks did. Many Romans did too. Benjamin Franklin did.”

“It’s not just Hindus and Buddhists,” Weiss said. “There is a Jewish tradition and Kabbala. Mystical Christianity. Plato believed in it. Ancient Greeks did. Many Romans did too. Benjamin Franklin did.”After treating hundreds of patients with regression therapy, Finkelstein, who runs the Malibu Wholistic Health Center, came away convinced that Laird wasn’t lying and wasn’t psychotic.

Indeed, he noted, she was able to answer — under hypnosis — hundreds of carefully researched questions about Monroe’s life. He noted that some of her answers could have been known only by the real Monroe, such as being able to identify the actress’ maternal aunts in a family photograph.

The psychiatrist also pointed out similarities that he said existed between the two women’s facial features, hands, feet, voice patterns and handwriting. Finkelstein stressed that Laird was not a poser who wanted to embody Monroe but was someone struggling to reconcile years of pain and disturbing memories: “She didn’t want to be Marilyn Monroe, period. She wanted to be herself, unlike so many pretenders, beautiful girls who stepped forward and wanted to be her.”

In some ways, Laird’s account is reminiscent of the 1956 bestseller “The Quest for Bridey Murphy.”

In that book, late author Morey Bernstein, who was a Colorado businessman and amateur hypnotist, wrote about placing a 29-year-old housewife named Virginia Tighe under hypnosis. At a certain point, she began speaking in a thick Irish brogue and, over several sessions, described her life as a woman named Bridey Murphy, who was born in 1798 near Cork, Ireland. These sessions garnered headlines and captivated the public’s imagination — how could Tighe have conjured up such vivid details about a rural life in Ireland? How could she carry off a brogue? The fact that ensuing investigations failed to prove that Bridey Murphy actually existed in Ireland at that time did nothing to quell the public’s interest.

Finkelstein gravitated into New Age beliefs after being schooled in traditional psychiatry.

Finkelstein, who was born in Romania, received his medical degree in Israel, then moved to America, where he took his residency and fellowship training at the Menninger School.

Finkelstein said it was during the mid-1970s, while he was an assistant professor of psychiatry at Rush Medical School and the University in Chicago, that he grew frustrated with psychoanalysis. He writes in his book that “one early morning I had an overwhelming personal experience, a spontaneous recall of one of my past lives.” (In one of those lives, Finkelstein said, he was a physician in medieval France.)

Finkelstein said his colleagues at Rush weren’t enamored of his unorthodox views. “They didn’t fire me or anything, but I sensed what they were about to do,” he said with a chuckle, “so I sort of, you know, got behind bushes and ducked so I could do my work” in private practice. From 1977 to 1980, while in private practice in Palatine, Ill., he notes in his book, he conducted a research study on volunteers involving more than 700 regressions.

In the fall of 1998, long after moving his practice to California, Finkelstein received an e-mail from Laird. In the book, she describes how she had visited a psychiatrist in Canada, who asked her to write down what she thought was wrong with her.

At the bottom of the page, she wrote: “I think I’m Marilyn Monroe.” She was given pills and sent home. Around that time, Laird began scouring the Internet, looking for a doctor who believed, as she now did, in past lives. There, she found Finkelstein’s website.

Laird said she was 11 or 12, wondering aloud about the beauty mark above her lip, when her aunt began singing “A kiss on the hand may be quite continental, but diamonds are a girl’s best friend.” When Laird asked where the song was from, her aunt replied it was sung by Marilyn Monroe in the movie “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.”

Up to that point, Laird said, “I didn’t know what [Monroe] looked like or who she was, but it was just like an explosion in my mind.”

As the years passed, Laird said, she experienced terrifying flashbacks and dreams of Monroe that sent her spiraling into drugs and alcohol and even a psychiatric ward. She said she was afraid and ashamed to tell anyone about her beliefs. She said she hadn’t even told her mother or her boyfriend that she believed she was the reincarnation of Marilyn Monroe until the eve of the recent book publishing.

Laird said she did not dress up like Monroe or impersonate her, although she did agree to pose as the late actress for some photos for the book as a way to draw comparisons with what Finkelstein says are the similarities between the two women. Laird also insisted she was not trying to cash in on Finkelstein’s book and has not been paid for her work on the book, nor would she share in any profit from sales. She also said her fellow band members were concerned about her coming forward at this time for fear that it would hurt the group’s credibility. (That said, they will be performing in Los Angeles this week after she makes the rounds of news conferences and talk shows to promote the book on the eve of the anniversary of Monroe’s death.)

Laird said she had a passing knowledge of Monroe but had never done the kind of research that might explain the persistent familiarity she felt for Marilyn.

Laird described past life regression as “creepy and horrible.” But she said it had rid her of her demons. “Afterward, you are exhausted,” she said. “I don’t want to scare people. I really am an advocate, but physically, it’s horrible.”

Lying on her back, eyes closed, her dyed blond locks splayed around her shoulders, Laird spent hours under hypnosis last year in her hometown of Toronto, where Finkelstein traveled to treat her.

At a session conducted last Nov. 11 and recounted in the book, Finkelstein asked the hypnotized Laird what happened on the night of Aug. 4, 1962, that led to Marilyn’s death inside her Brentwood home.

“Was it an accident, or were you murdered in this life as Marilyn?” Finkelstein asked Laird. “And, if so, by whom?”

“By me,” she replied.

“By yourself?”

“Yes.”

Laird, still speaking as Marilyn, went on to say: “I’m not murdered.”

Laird also said that her love affair with JFK began as early as 1954 and didn’t end until two months before the actress’ death. She recalled driving with the future president in either 1957 or 1958 and how they were “playing around” and “touching” while in the car.

Her face contorted, her body trembling, the hypnotized Laird gripped Finkelstein’s hand tightly as she cried out: “I don’t want him [JFK] to leave me. My arms are numb. Help me, help me, help me! Help me, help me!”

Connected at birth?

LAIRD was born 11 months after Monroe’s death. But Laird said she doesn’t believe that contradicts her reincarnation theory. Laird said her mother suffered a miscarriage and two months later became pregnant. “The same baby was me,” Laird said. “She lost me, but I came back.”

Finkelstein came to another startling conclusion that may be harder to swallow, for some, than Sherrie Laird being Marilyn Monroe.

He believes her daughter, Kezia, is the reincarnation of Gladys Baker, Monroe’s mother.

He noted that Kezia was conceived within days of Baker’s death in 1984.

“It seems that immediately upon her death, Gladys made a ‘reservation’ to be born to Sherrie,” Finkelstein writes in his book.

“That’s his biggest gift for me,” Laird said in an interview. “[Kezia is] Gladys…. You actually do get a chance to work things out with loved ones.”

Laird is scheduled to attend a news conference with Finkelstein in Westwood on Friday to promote the book. The next day, on the 44th anniversary of Monroe’s death, Finkelstein said they plan to visit the actress’ crypt at Westwood Memorial Park, where fans gather annually to commemorate her.

Laird said she was initially “plagued with doubts” about going public with her story.

“I want to be known for my singing. What am I going to do, go around posing as Marilyn? That’s like a shoddy impostor. That is not me.”

Times correspondent Jennifer Byrne contributed to this article.