By Jake Whitman and Cynthia McFadden

It’s not unusual for little boys to have vivid imaginations, but Ryan’s stories were truly legendary.

His mother Cyndi said it all began with horrible nightmares when he was 4 years old. Then when he was 5 years old, he confided in her one evening before bed.

“He said mom, I have something I need to tell you,” she told TODAY. “I used to be somebody else.” The preschooler would then talk about “going home” to Hollywood, and would cry for his mother to take him there.

His mother said he would tell stories about meeting stars like Rita Hayworth, traveling overseas on lavish vacations, dancing on Broadway, and working for an agency where people would change their names.

She said her son even recalled that the street he lived on had the word “rock” in it.

“His stories were so detailed and they were so extensive, that it just wasn’t like a child could have made it up,” she said.

Cyndi said she was raised Baptist and had never really thought about reincarnation. So she decided to keep her son’s “memories” a secret— even from her own husband.

Privately, she checked out books about Hollywood from the local library, hoping something inside would help her son make sense of his strange memories and help her son cope with his sometimes troubling “memories.”

“Then we found the picture, and it changed everything,” she said.

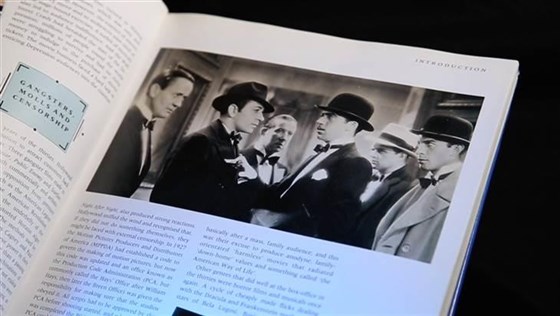

That photo, in one of the books from the library, was a publicity shot from the 1932 movie “Night After Night,” starring Mae West in her film debut. “

She turns to the page in the book, and I say ‘that’s me, that’s who I was,’ Ryan remembers.

Cyndi said she was shocked, and only more confused, because the man Ryan pointed to was an extra in the film, with no spoken lines.

But finally she had a face to match to her son’s strange “memories,” giving her the courage to ask someone for help.

That someone was Dr. Jim Tucker, M.D., the Bonner-Lowry Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Neurobehavioral Sciences at the University of Virginia.

The child psychiatrist has spent more than a decade studying the cases of children, usually between the ages of 2 and 6 years old, who say they remember a past life.

In his book, “Return To Life,” Tucker details some of the American cases he has studied over the years, including Ryan’s.

“These cases demand an explanation,” Tucker said, “We can’t just write them off or explain them away as just some sort of normal cultural thing.”

Tucker’s office contains the files of more than 2,500 children— cases accumulated from all over the world by his predecessor, Ian Stevenson. Stevenson, who died in 2007, began investigating the strange phenomena back in 1961, and kept detailed interviews and evidence on each case.

Tucker has painstakingly coded the handwritten files, discovering intriguing patterns. For instance, 70 percent of the children say they died violent or unexpected deaths in their previous lives, and males account for 73 percent of those deaths— mirroring the statistics of those who die of unnatural causes in the general population.

“There’d be no way to orchestrate that statistic with over 2,000 cases,” Tucker said.

Tucker said the majority of children he has investigated say they remember average lives— rarely do they claim memories of someone famous.

He said Ryan’s case is one of his most unusual because of the incredible detail he was able to provide.

Tucker, with help from researchers working on a documentary tried to identify the man Ryan pointed to in the book about Hollywood.

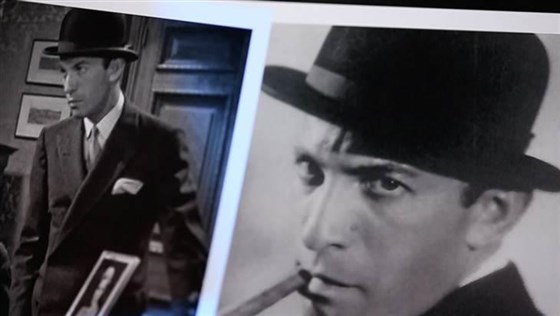

After weeks of research, a film archivist combing through original production materials for the movie “Night After Night” was able to confirm who he was. His name, Marty Martyn, a former movie extra who later became a powerful Hollywood agent and died in 1964.

“If you look at a picture of a guy with no lines in a movie, and then tell me about his life, I don’t think many of us would have come up with Marty Martyn’s life,” Tucker said, “Yet Ryan provided many details that really did fit with his life.”

After digging through old records— almost none of them available on the internet, and tracking down Martyn’s own daughter, Tucker was able to confirm 55 details Ryan gave about his life.

It turns out Martyn wasn’t just a movie extra. Just as Ryan said, he had also danced on Broadway, traveled overseas to Paris, and worked at an agency where stage names were often created for new clients.

Tucker also discovered Ryan’s claim that he lived on the street with the word “rock” in it was nearly spot on— Martyn lived at 825 North Roxbury Dr. in Beverly Hills.

Tucker was also able to confirm other obscure facts that Ryan gave— how many children Martyn had, how many times he was married, even how many sisters he had. While Martyn’s own daughter grew up thinking her father had just one sister— Tucker was able to confirm he actually had two, again, just as Ryan claimed.

Dr. Tucker’s research is not without critics. When his work was recently featured in The University Of Virginia Magazine, some readers shared their outrage in the comments section. One reader wrote he was “appalled” that this kind of work is being done at the university. Another called Tucker’s research “pseudoscience.”

Tucker said he’s only trying to apply the rules of science to the mystery of reincarnation. Even with Ryan’s case, there was one fact the detailed obsessed scientist thought the little boy had wrong.

“He said he didn’t see why God would let you get to be 61 and then make you come back as a baby,” Tucker said.

That statement seemed to be incorrect because Martyn’s death certificate listed his age as 59 years old when he died.

But as Tucker dug deeper, he was able to uncover census records showing Martyn was In fact born in 1903 and not 1905, meaning Ryan’s statement — not his official death certificate— was indeed correct.

Now that Ryan is 10 years old, he said his memories of Marty Martyn’s life are fading, which Dr. Tucker said is typical as children get older. Ryan said while he he’s glad he had the experience, he’s also happy to put to move on, and just be a kid.