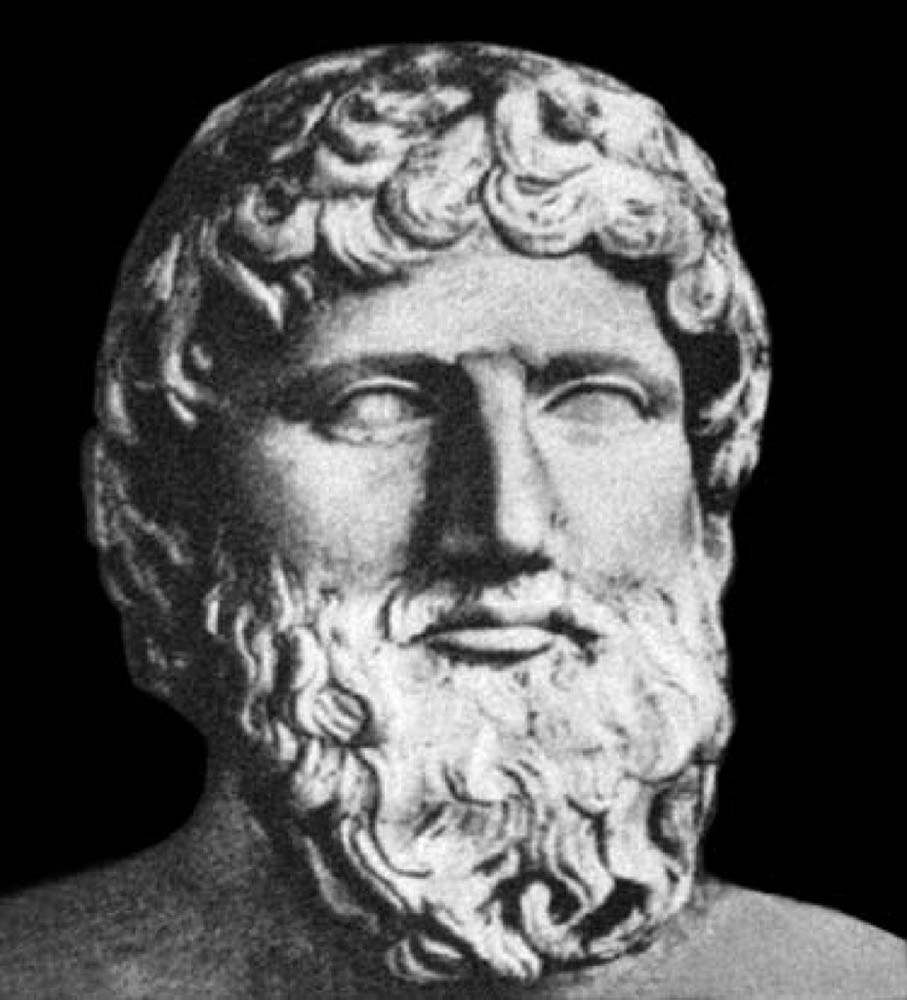

Plato

I am confident in the belief that there truly is such a thing as living again, and that the living spring from the dead, and that the souls of the dead are in existence, and that the good souls have a better portion than the evil. - PlatoPlato

The idea of reincarnation was not unknown to the ancient Greeks. The eminent philosopher Plato was a major exponent of this belief (as was Pythagoras and the Orphic mystery religion(s)). Plato attributed the idea back to his mentor Socrates, who he recounts saying upon his deathbed.

In The Republic Plato develops this idea of the living coming from the dead even further. The Myth of Er is a story Plato has Socrates tell his audience, Glaucon, about Er, a man chosen to witness the workings of the Underworld. Plato uses this story to support his theories that humans have an immortal soul that will be reincarnated, and that despite destiny they still have a modicum of control.

Men and women gathered around the stacked wood that made up the funeral pyre. Er was placed atop, he looked as if he was sleeping, his body showing no sign of decay despite being 12 days dead. Just as the flickering ember was drawn near, there was sudden movement as Er stirred, then sprung awake, anxious to tell of what he had witnessed. Er recounted that, on the moment of his death, his soul had left his body and joined up with a stream of other, recently departed ones. All of these souls were instinctively heading in the same direction. Eventually they arrived at their mysterious destination, a place that had two tunnels ascending to the heavens and two others descending below. Between these sat the panel of judges, writing the deeds of each man as he came forth. Those that were just had their good deeds pinned to their front, and were invited to ascend to the heavens through the right-hand path. Those that had sinned had their trespasses pinned to their backs instead, and were sent down the left-hand path.

As Er watched, a messenger approached. He pulled Er aside and told him that he would not be judged just yet, as he been chosen to return to the living to forewarn them of all he had seen. He gestured towards the meadows and Er noticed that the other tunnels were in use too. Souls would emerge from the heavens all shining and bright, while others would haul themselves up from the bowels of the earth, disheveled and dusty. Once expelled, both clean and dirty alike would gather on the grassy hills; some hugging, some chatting, some sobbing. Er made his way over, talking to the others as he went. Each soul had a different story: some had tales of beauty and wonder, while others told of inconceivable horrors. As he walked Er learned the souls were sentenced to experience ten times over what had been done in life, and were rewarded and punished accordingly. Once that was completed the souls would be returned to the middle-world where they gathered in the meadows to rest.

Er waited beside them, and when seven days had passed, the company began to move. Over a number of days they journeyed through the underworld until they reached the place where the daughters of Necessity, the Moirai (the Fates), ruled. There they were to receive their new allotment of fate from Lachesis, the sister who determined the length of their thread of life (Her sister Clotho spun the threads while her other sister, Atropos, cut them from the wheel). Before Lachesis a prophet stood upon a pulpit, announcing to those assembled:

“Hear the word of Lachesis, the daughter of Necessity. Mortal souls, behold a new cycle of life and mortality. Your genius will not be allotted to you, but you choose your genius; and let him who draws the first lot have the first choice, and the life which he chooses shall be his destiny. Virtue is free, and as a man honors or dishonors her will have more or less of her; the responsibility is with the chooser –God is justified.”

With that the man tossed the lots into the waiting crowd, and each gathered up the one that fell at their feet. The man who drew the first lot went first, and approached the pile of lives woven by the fates. Immediately, he grabbed the brightest one he saw; the life of a dictator. His head filled with visions of power and wealth, and the conquests he would make. But as he held it closer and reflected on his choice he began to cry out in despair. He saw that he was fated to devour his own children in an effort to cement his powerful reign, much like Cronus. Once all the souls had chosen their new lives, they passed the sisters who wove their fates upon them, and out through the spindle of necessity.

From there they reached the plain of forgetfulness, an arid land which the river of Unmindfulness (Lethe) ran through. They spent the night camped on its banks where every soul except for Er’s was obliged to drink from the waters. The wise drank sparsely, wanting to take shadows of remembrance and wisdom into their next lives, but many drank greedily, unable to resist the cool waters in the barren heat. As they lay down to sleep, they felt a thunderstorm, followed by an earthquake as they were all propelled towards their next life, or in Er’s case, to reawaken in his former one.

Plato’s theory of re-incarnation is interesting, especially as it challenges established notions of fate and destiny. He tempers the idea of fate being inevitable by introducing the concept of choice, which bears striking parallels with the Bardo Thodol, the Tibetan Book of the Dead. Foolishness is often born from the follies of human nature, and Plato demonstrates this as each person chooses their new life. The first man to choose was blinded by the external ideas of power and wealth. He did not pause to consider the trials that come with holding power, nor the corruption that often goes hand in hand with it, and the full realization of his choice left him distraught.

The complete text includes many of the other choices from people of note; their earlier lives spurring them to choose unwisely. For example: Orpheus, angry after being torn apart by a mob of women, elects to be reborn as a swan (humans can re-incarnate as animals and vice-versa). He does this not out of desire to be a swan, but because his anger means that he does not want to borne from a woman, which was part of the Greek understanding of swan biology. Similarly, Agamemnon chose to be an eagle because of his hatred of humankind. For both of these men, the depths of their anger destroyed their humanity. Odysseus on the other-hand chose wisely. Despite the fact that he received the final lot, he carefully sorted through those discarded by the others. Tired after his life of adventure, Odysseus knew the value of a settled life that he could comfortably live out in peace and quiet. When he finally came across the life of a common man (one that all the others had viewed as worthless) he happily took it for himself.

The second choice given by Plato was the amount of water to drink at the river Lethe. While each had to drink enough to remove their knowledge of their previous lives, Plato implies that wisdom could remain:

“they encamped by the river of Unmindfulness, whose water no vessel can hold; of this they were all obliged to drink a certain quantity, and those who were not saved by wisdom drank more than was necessary; and each one as he drank forgot all things”.

While the souls cannot return to life with the memories of the underworld there is an inherent suggestion that by imbibing in excess, they choose to forget some of the innate wisdom and knowledge they may otherwise have been born with. Again, this is a choice; free-will is the primary determining factor.

Plato’s theory of reincarnation retains notions of fate and destiny , but moderates it with a sense of self-accountability. At some point, despite the fact we cannot remember our past existences, we chose the life we live and our allotment of wisdom, and that is the life we must lead in this iteration. The only measure of control lies in our ability to live as justly as possible, and hopefully to make a better choice the next time round.