Aged five, Carl Edon loved to draw. He spent hours working on dot-to-dots or his colouring books, and drawing his own shapes and patterns.

One morning, his mother, Val, noticed how long he had been working on a picture and asked to take a look.

It was surprisingly neat, not a scribble, yet she could not quite make out what the designs were meant to be.

Carl explained that these were his air force badges. The first was an eagle, its wings drawn straight out at the sides.

But before Carl could describe the next symbol, Val recognised it with a jolt. It was a swastika.

Perhaps even more extraordinary was the picture that his father Jim found in Carl’s bedroom just after his son’s sixth birthday. It showed the cockpit of a plane, complete with all the gauges, instruments and levers.

Carl pointed out a red pedal at the bottom: this was the handle to drop the bombs, he said, adding that it was a Messerschmitt bomber like the one he had flown in the war.

It was not the first time the boy had claimed to remember a past life as a German pilot. As young as two, he would wake from vivid dreams, screaming that his plane had crashed, his leg was svered and he was bleeding to death.

These were horrific nightmares for a boy so young — and, more eerie still, Carl refused to accept they were just dreams.

Perhaps even more extraordinary was the picture that his father Jim found in Carl’s bedroom just after his son’s sixth birthday. It showed the cockpit of a plane, complete with all the gauges, instruments and levers.

Carl pointed out a red pedal at the bottom: this was the handle to drop the bombs, he said, adding that it was a Messerschmitt bomber like the one he had flown in the war.

It was not the first time the boy had claimed to remember a past life as a German pilot. As young as two, he would wake from vivid dreams, screaming that his plane had crashed, his leg was severed and he was bleeding to death.

These were horrific nightmares for a boy so young — and, more eerie still, Carl refused to accept they were just dreams.

From the moment Carl Edon was born, his mother sensed there was something different about himHe decided to test Carl a little more. ‘So what uniform did you wear?’ he asked. Carl replied without hesitation: ‘Grey trousers, tucked into knee-high leather boots and a black jacket.’

A few days later, Jim visited the local library in Middlesbrough, North Yorkshire, clutching the pictures Carl had drawn.

In the history section he pulled out any books he could find on the German Luftwaffe of World War II. With the books laid out in front of him, he sat in total shock.

It was all there. The picture of the cockpit, the badges, the description of the uniform: everything was exactly as Carl had described. There was even a Messerschmitt bomber — the 110.

The legend of a crashed German bomber had a special significance for the people of Middlesbrough. On January 15, 1942, after a German attack on merchant ships in the North Sea, a stricken Luftwaffe plane attempted a crash-landing outside the town and ploughed straight into an anti-aircraft cable, a thick metal line securing a barrage balloon.

The cable sheared off one wing, and the aircraft smashed into the ground. The fireball was so intense that it was half an hour before firemen could get close. The next morning the wreckage lay in a smouldering crater, amid 100ft of smashed railway track.

Rescue workers, watched by two intelligence men in thick woollen coats, pulled three charred bodies from the plane.

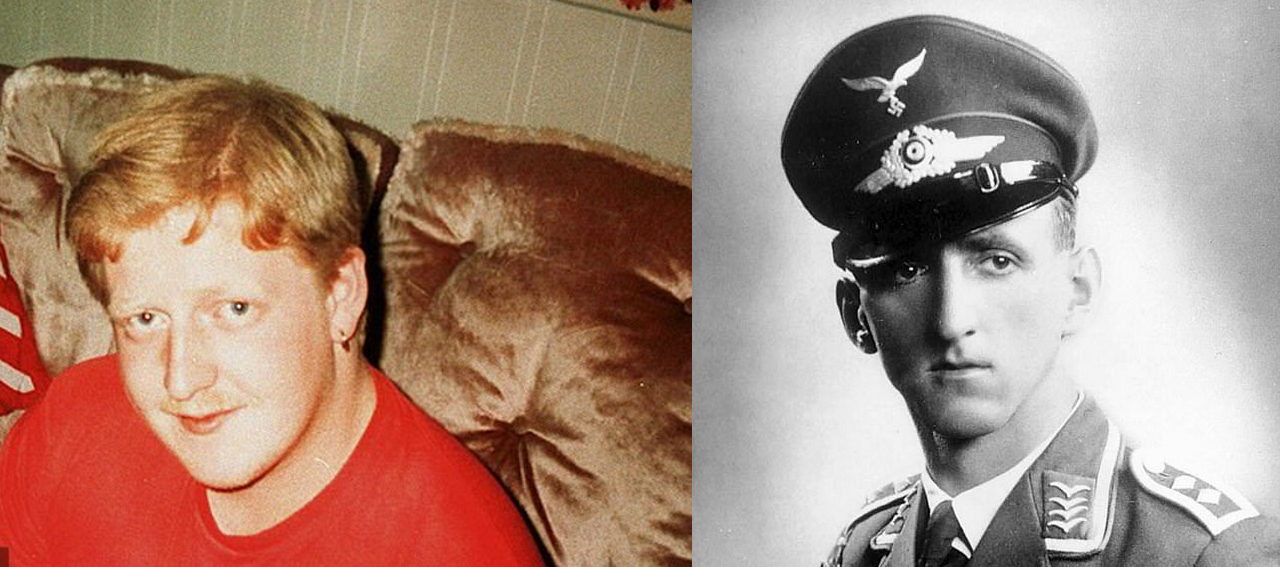

World War Two German bomber Heinrich Richter, who Carl Edon believed he was during a past life